Health and social responses: drug consumption rooms

Introduction

This page provides an overview of key issues related to drug consumption rooms, including service delivery, guidance and existing evidence and latest developments in Europe. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Last update: 24 April 2024.

In a nutshell

Service aims usually include:

- reducing morbidity and mortality,

- referral to other care services,

- reducing public nuisance,

- engaging people with high-risk patterns of use.

Target population:

- people who are not able or willing to stop consuming drugs and engage in risky drug use behaviours,

- people who use drugs with limited opportunities for hygienic injection or inhalation.

Services which may be provided:

- professional supervision of consumption,

- a safer environment for drug use,

- provision of sterile or hygienic injecting and smoking equipment,

- emergency intervention in overdoses that occur on-site,

- counselling services,

- primary medical care,

- advice or training for clients in safer forms of drug use, overdose awareness and the use of naloxone,

- opioid agonist treatment,

- referral of clients to appropriate social, healthcare and treatment services,

- refreshments, use of a phone, Wi-Fi, and the possibility to shower and wash clothes.

Basics

What are drug consumption rooms?

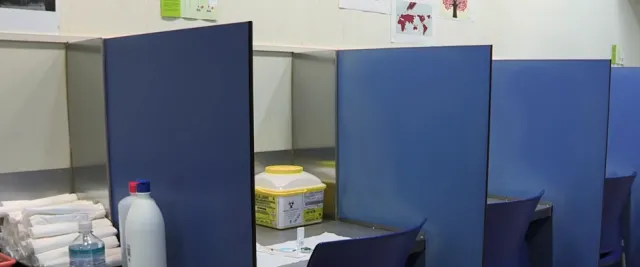

Drug consumption rooms, sometimes known as supervised injecting facilities, have been defined as professionally supervised healthcare facilities, where people who use drugs can do so in safer and more hygienic conditions (Hedrich et al., 2010). Importantly, they aim to offer hygienic conditions, often supervision by medically trained staff, and a safe environment where people can use drugs without fear of arrest or legal repercussions.

What are their aims?

Drug consumption rooms are generally established with the aim of addressing a mix of individual health, public health and public order objectives. These services typically aim to reach out to and maintain contact with the most marginalised populations of people who use drugs – those experiencing high barriers to accessing medical and social support – and to provide a gateway through which these groups can connect with a broader range of health and social support services.

Drug consumption rooms further seek to reduce overdose-related morbidity and mortality and prevent the spread of infectious diseases by offering access to sterile equipment, safer use advice and emergency interventions (Belackova et al., 2018).

By giving people who use drugs the opportunity to consume in a calm, hygienic and supervised environment, drug consumption rooms also aim to reduce harms resulting from the broader ‘risk environment’ that socially marginalised or excluded groups may be exposed to as a consequence of multiple interacting physical, social, economic and policy factors (Rhodes, 2002).

Drug consumption rooms are usually set up in areas near open drug scenes, which are characterised by high rates of public drug use. By providing a space for safe consumption that is sheltered from public view, they may also have the objective of reducing drug use in public and improving public amenities (e.g. through fewer improperly discarded syringes and less drug-use-related waste in general). In this respect, drug consumption rooms can be characterised as a response to public order and safety concerns regarding drug scenes, while creating an improved environment for local residents (Hedrich et al., 2010; Potier et al., 2014; Schäffer et al., 2014).

In addition, drug consumption rooms aim to play a role in combating stigma by treating people who use drugs with dignity and supporting them in multiple aspects of social integration, such as finding employment and housing (Kappel et al., 2016).

As frontline, low-threshold services, drug consumption rooms are often among the first to gain insights into unfamiliar drug use patterns and, therefore, can also have a role to play in the early identification of new and emerging trends among the high-risk populations using their services (EMCDDA and C-EHRN, 2023).

The specific goals and objectives of drug consumption rooms may differ significantly between and even within jurisdictions, as they are adapted to local needs and regulatory frameworks. This is also an intervention area that is rapidly changing, both in approach and in models of service delivery, and research and evaluation may be necessary to assess the effectiveness of this approach to new patterns of use.

Target groups

The primary target group for drug consumption room services are people who engage in risky drug use. Facilities for supervised drug consumption tend to be located in areas that are experiencing problems in terms of public use, including communities with open drug scenes, and are targeted at people who use drugs with limited opportunities for hygienic injection (e.g. people experiencing homelessness, including those living in insecure accommodation or shelters). They provide an alternative for people who would otherwise use in an environment where the risk of harm is high due to factors such as the need to administer drugs rapidly, using drugs alone, and sharing or reusing injecting equipment.

Drug consumption rooms are often embedded in a health or drugs facility, a drop-in centre or a shelter, and most supervised consumption facilities admit people who inject as well as those who smoke or inhale drugs (Speed et al., 2020). A limited number of facilities provide specialised support to women who use drugs, or have developed activities and interventions tailored to the needs of migrants or gender-diverse people (see Migration and drug use: health and social responses).

Service delivery

Models of service delivery

Two operational models are typically employed in Europe: (1) integrated drug consumption rooms, operating within low-threshold facilities, where the supervision of drug use is just one of several services offered; and (2) specialised drug consumption rooms, which provide a relatively narrow range of services directly related to supervised consumption. Drug consumption rooms may be located within a fixed site or provided as a mobile service. There is therefore no single operational model, with variations in organisation, staffing and service delivery reflecting both the availability of resources and the needs of the communities in which the drug consumption rooms are located, as well as local regulatory approaches (Belackova et al., 2018; Woods, 2014).

Integrated services

The most common set-up for a drug consumption room is as a physically co-located service, integrated within a healthcare facility, such as a community-based harm reduction centre, and functioning as part of its broader service portfolio, or as an adjunct service to an overnight shelter or other housing service. Here, the supervision of drug consumption is one of several harm-reduction and survival-oriented services offered within the same premises, which may include drop-in services with the provision of food, showers and clothing; shelter; a social room; psychosocial care; a drug-checking service; medical care, including wound care and voluntary testing for infections; advice, counselling and referral to treatment for substance use; and, in some cases, access to employment programmes.

Specialised services

Where large capacity is required, supervised drug consumption services may operate in the form of specialised stand-alone facilities. While they still function as part of a local network through which their clients can access further health and social services, they are physically separated. This type of provision typically offers a narrower range of services, directly related to supervised consumption, which includes providing hygienic drug use equipment and materials, advice on health and safer drug use, intervention in the case of emergencies and a space where people who use drugs can remain under observation after the consumption of a drug.

Core services directly related to supervised consumption may include:

- education on the harms of drug use, safer consumption practices and safer sex;

- the provision of sterile syringes, pipes and other drug use equipment and materials;

- supervision during, and observation following, drug use;

- safe disposal of used equipment;

- emergency medical care in the case of overdose or other adverse reactions;

- basic health services, for example wound care.

In a few locations, supervised consumption spaces are provided via outreach vehicles. This may be due to the need to respond to a more geographically dispersed population, or because of local resistance to the establishment of a fixed site, or because this kind of provision is less costly. Mobile drug consumption rooms consist of specially fitted vans or buses with typically one to three injection booths. They have the advantages of being less costly to set up and allowing greater flexibility in service delivery, as services can be provided to clients in more than one location. However, mobile drug consumption rooms are subject to limitations, such as the type of drug consumption that can be accommodated, which is usually restricted to injecting, as the supervision of drug smoking requires a separate compartment within the mobile unit equipped with an extraction system. Their operation can also be affected by the weather. Similar to specialised drug consumption rooms at fixed locations, mobile facilities usually work as part of a wider local network of services, and staff refer (and sometimes accompany) clients to other service providers, as required.

What typically happens at a drug consumption room?

Clients of drug consumption rooms bring their own pre-obtained drugs and consume them in the presence of staff. Depending on the site, drugs are injected, snorted/sniffed, inhaled/smoked or consumed orally. Trained staff are available to provide advice on safer injection practices, including recommendations on the selection of injection site and techniques, as well as information on less risky practices. During and after the consumption process, staff monitor clients for signs of overdose or other adverse events so that they can provide assistance if required. Staff will intervene if there is an accidental overdose or if clients experience physical or mental distress for other reasons (e.g. cardiac arrest or an allergic reaction).

The space where drug consumption takes place is physically separated from other parts of the facility, and access to it is controlled. Before entering, staff assess what substance the person is planning to use, provide hygienic drug equipment and offer advice on safer use as required. After consumption, the client usually remains under observation (some drug consumption rooms have a recovery area that clients can move to after consumption).

In addition, drug consumption rooms typically provide a wide array of services, which may include low-threshold access to social, medical and mental healthcare and support, or drug checking. Among a range of survival-oriented services and on-site assistance, clients may be assessed as to their need for referral to further healthcare services, including voluntary drug treatment. Mobile facilities do not usually provide the same range of services due to the more limited physical space.

Access to consumption facilities may be restricted to registered clients, and often certain conditions must be met, such as minimum age or local residency. House rules will vary, but typically they will prohibit violence, drug dealing and drug sharing on the facilities. Staff are usually not allowed to assist clients in administering their drugs.

Opening hours and the number of daily visits allowed vary considerably across jurisdictions and between facilities.

Considerations for implementation

Drug consumption rooms either operate as a unit within a public healthcare facility (health centre, hospital), or – more commonly – are run by a non-governmental organisation. As with other harm reduction interventions, their primary source of funding is usually local government.

Existing legal frameworks are an important consideration for the establishment of a new drug consumption room and can prove problematic in some cases. Depending on the host country, official endorsement of the provision of drug consumption rooms as a health service may be based on a number of different regulatory frameworks or legal approaches. Examples include legal expert opinion (Körner, 1993), guidelines from the attorney-general, specific provisions or exemptions in national drug laws, or existing local public health regulations. Not all countries permit the establishment of drug consumption rooms. To date, there are more than one hundred legally sanctioned drug consumption rooms operating in cities in some EU and other European countries, as well as in Australia, Canada, Mexico and the United States.

Drug consumption rooms are mostly set up in urban settings that are experiencing problems related to public drug use and overdose. As with other drug services, investment in consulting and reaching a consensus with key local actors will be a critical element, necessary for minimising any potential community resistance or counter-productive police responses (Jauffret-Roustide and Cailbault, 2018; Taylor et al., 2019). In addition, developing a common understanding of the current drug situation is important, both for building a consensus on the health and social needs of people who use drugs, and for effectively addressing issues of concern for the local community and institutional stakeholders.

Multi-agency local partnerships or neighbourhood committees have also been identified as important ingredients in successfully setting up and running a drug consumption room. These typically take the form of local ‘round-tables’ of actors drawn from health and law enforcement, which are chaired by the city administration and work alongside the facility to ensure that good communication is established between all the stakeholders and coherent messages are relayed to the media (see Figure Composition of a drug consumption room neighbourhood committee). The roles of these committees may include monitoring the quality of life in the neighbourhood, mediation when problems arise that involve the facility or its clients, and sometimes implementing a broader action plan for the local community as part of an urban policy concept (Jauffret-Roustide and Cailbault, 2018).

Staff and peer engagement

Drug consumption rooms are typically staffed by nurses, social workers, peer workers and health educators, but doctors and security staff may also be part of the team. Other professional groups may also be represented (Belackova et al., 2018; EMCDDA and C-EHRN, 2023).

Depending on the drug consumption room, the staff’s tasks may include the reception of clients; visual inspection of the substances to be consumed (or in some cases drug checking); and the overall evaluation of the client. Drug consumption rooms provide sterile syringes and other drug use equipment as required; answer questions about substances and safe consumption practices; provide education on safer drug use practices; monitor clients for potential overdose; and, if necessary, intervene in the case of adverse events.

Typically, nurses and other staff are not permitted to administer injections, but provide education on safer injecting, including on-site demonstrations of safer injecting techniques. Staff may be allowed to help clients to find a vein for safer injecting, but may not handle any drugs they bring into the facility. After consumption, staff continue to monitor clients for signs of distress.

Typically, the staff responsible for welcoming and registering clients collect specific pre-defined data, such as basic personal information, and attribute a unique identification number or code to each individual. They may also collect additional data regarding each visit, such as the time of day and the drug used. In some facilities, staff collect data through cross-sectional surveys in order to document trends in the well-being of individual clients, particularly information on health and health-related behaviour, as well as access to and use of drug rehabilitation programmes and primary and secondary healthcare facilities.

The duties of staff in response to drug-related emergencies are usually defined in site-specific operational protocols. Staff are usually trained to administer naloxone in response to an opioid overdose and are instructed to contact emergency services if a client experiences an overdose.

Evidence and guidance

As services, drug consumption rooms are particularly challenging to evaluate. This is not helped by the low number of studies using similar designs. Assessment in this area is difficult because of different definitions used by reviews, or in the research questions addressed, as well as the heterogeneity of outcome measures adopted (EMCDDA and C-EHRN, 2023). Collectively this hinders the pooling of results from original studies and prevents systematic reviews from producing strong evidence statements.

Lack of evidence, or a body of low-quality evidence, does not necessarily mean that an intervention is ineffective. It merely shows that the intervention has not yet been adequately studied. There is also a high degree of uncertainty in interpreting the results of studies with low-level evidence and a possible high risk of bias.

Taking into consideration current evidence reviews (EMCDDA and C-EHRN, 2023), alongside the general principles of evidence-based research and decision-making (see Spotlight on… Understanding and using evidence), the existing evidence is suggestive of a beneficial effect for drug consumption rooms on a number of outcomes (see Table Overview of the evidence concerning drug consumption rooms). These include improving access to healthcare and harm reduction services for hard-to-reach target populations (Levengood et al., 2021; Pardo et al., 2018; Potier et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2021); reducing drug-related deaths (Belackova et al., 2017; Kimber et al., 2010; Levengood et al., 2021; Pardo et al., 2018; Potier et al., 2014; Roux et al., 2023; Semaan et al., 2011); and reducing injecting risk behaviours (Belackova et al., 2017; Belackova et al., 2018; Bravo et al., 2009; Kimber et al., 2010; Levengood et al., 2021; Milloy and Wood, 2009; Pardo et al., 2018; Potier et al., 2014; Roux et al., 2023; Semaan et al., 2011).

In addition, a recent expert panel review supports the provision of supervised injecting facilities to reduce injecting risk behaviour among people who inject drugs, which could as a consequence contribute to the prevention of HCV and HIV transmission (ECDC and EMCDDA, 2023).

There is also some evidence to suggest that drug consumption rooms have been found not to increase crime in the surrounding area and may contribute to reducing drug use in public spaces and alleviating overall public nuisance in areas in which high levels of public drug use occur (Belackova et al., 2017; Levengood et al., 2021; Potier et al., 2014; Tran et al., 2021).

In spite of the difficulties of conducting research in this area, more studies are needed to improve the body of evidence on the effectiveness of drug consumption rooms in reducing individual and community-level harms, as well as in improving outcomes associated with both drug injecting and non-injecting routes of administration, and those related to public nuisance or medical costs.

Overview of the evidence concerning drug consumption rooms

| Statement | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Quality | |

|

Drug consumption rooms can be effective in reducing drug-related deaths. |

Beneficial |

Low |

|

Drug consumption rooms may play a role in reducing injecting risk behaviours. |

Beneficial |

Low |

|

Drug consumption rooms may have a beneficial impact in helping hard-to-reach target populations to access healthcare services and harm reduction services. |

Beneficial |

Low |

|

Drug consumption rooms are effective in reducing drug use in public spaces as well as reducing overall public nuisance. |

Beneficial |

Low |

|

Drug consumption rooms do not increase crime in the surrounding area. |

Beneficial |

Low |

Evidence effect key:

Beneficial: Evidence of benefit in the intended direction. Unclear: It is not clear whether the intervention produces the intended benefit. Potential harm: Evidence of potential harm, or evidence that the intervention has the opposite effect to that intended (e.g. increasing rather than decreasing drug use).

Evidence quality key:

High: We can have a high level of confidence in the evidence available. Moderate: We have reasonable confidence in the evidence available. Low: We have limited confidence in the evidence available. Very low: The evidence available is currently insufficient and therefore considerable uncertainty exists as to whether the intervention will produce the intended outcome.

European picture

Among other measures to reduce cases of fatal and non-fatal overdose, the EU Drugs Action Plan 2021-2025 calls for drug consumption rooms to be introduced, maintained or enhanced where appropriate and in accordance with national legislation. Nevertheless, in some countries drug consumption rooms are not currently permitted.

In Europe, they have been operating since 1986, when the first one was established in Bern, Switzerland. Since then, such facilities have been opened in cities in an increasing number of European countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal and Spain.

The geographical distribution of drug consumption rooms is uneven, both at the international and regional levels. More than one hundred drug consumption rooms are in operation globally, with services in some EU and other European countries, Australia, Canada, Mexico and the United States. The figure Location and number of drug consumption facilities throughout Europe provides an overview of the geographical location of drug consumption rooms across the European Union and Norway.

In Europe as a whole, the injection of heroin has been on the decline for a number of years and in some countries has been superseded by the misuse of synthetic opioids or stimulants, or both. Within this dynamic context, many drug services, including drug consumption rooms, have had to adapt their services to the changing needs of local populations and developments in the drug market; this often implies addressing a broad range of practices and harms. This has included, in some countries, providing spaces for non-injecting routes of administration, most commonly smoking, and allowing the consumption of a wider range of substances within the facility.

Implications for policy and practice

Basics

- Drug consumption rooms are healthcare facilities that seek to offer spaces for the supervised consumption of illicit substances. They are usually intended as a local response to local problems and needs.

- Drug consumption rooms primarily aim to prevent drug overdose deaths, reduce the risks of disease transmission through unhygienic injecting, and connect people who use drugs with addiction treatment and other health and social services.

- In general terms, two operational models are typically used in Europe: integrated services that operate within low-threshold facilities; and specialised services, offering a narrower range of services directly related to supervised consumption.

- While originally focused on drug injection, more recently other drug use behaviours have been targeted, such as smoking or inhaling.

- The diversity in programme design and the dynamic nature of service development in this area mean that generalisations need to be made with caution.

- In some EU countries, drug consumption rooms are not currently permitted.

Opportunities

- As frontline, low-threshold services, drug consumption rooms may be among the first to gain insights into new drug use patterns and, thus, have a role to play in the early identification of new and emerging trends among the high-risk populations using their services.

- As injection of heroin decreases in some countries, drug consumption rooms may shift their focus to the reduction of harms associated with other routes of administration (e.g. smoking) or other substances (e.g. cocaine, methamphetamine, GHB). Research and evaluation are particularly needed to assess the effectiveness of this approach with non-injecting populations.

- Drug consumption rooms may be a useful setting for implementation research to develop and improve prevention, harm reduction and public health strategies. Their closeness to consumption processes may allow the observation of individual risk behaviours and the evolution of risk behaviour over time.

Gaps

- High-quality research is needed to improve the evidence on the extent to which drug consumption rooms reduce individual and community-level harms, both for outcomes associated with drug injecting and those associated with non-injecting routes of administration.

- Implementation research and guidance is needed to better inform decision-makers intending to establish new drug consumption room services.

- There is a lack of provision and research on alternative models of service delivery, for example, services tailored to specific subpopulations such as women and migrants.

Further resources

EMCDDA

- Drug consumption rooms. Joint EMCDDA and C-EHRN report, 2023.

- Topic hub page: Drug consumption facilities.

- EMCDDA webinar: Drug consumption rooms in Europe – different realities, challenges and what to expect from the future, 2022.

- Spotlight on… Drug consumption rooms, 2022.

Other resources

- International Network on Health and Hepatitis in Substance Users (INHSU). Policy brief: how supervised consumption sites can save lives and improve local communities.

- Correlation – EHRN, Factsheet: Drug consumption rooms, 2020.

References

Belackova, V., Salmon, A. M., Schatz, E. and Jauncey, M. (2017), Online census of drug consumption rooms (DCRs) as a setting to address HCV: current practice and future capacity, International Network of Drug Consumption Rooms, Correlation Network, Uniting Medically Supervised Injecting Centre, Amsterdam, Sydney.

Belackova, V., Salmon, A. M., Schatz, E. and Jauncey, M. (2018), ‘Drug consumption rooms (DCRs) as a setting to address hepatitis C: findings from an international online survey’, Hepatology, Medicine and Policy 3, p. 9, doi:10.1186/s41124-018-0035-6.

Bravo, M. J., Royuela, L., De la Fuente, L., Brugal, M. T., Barrio, G. and Domingo-Salvany, A. (2009), ‘Use of supervised injection facilities and injection risk behaviours among young drug injectors’, Addiction 104(4), pp. 614-619, doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02474.x.

ECDC and EMCDDA (2023), Prevention and control of infectious diseases among people who inject drugs: 2023 update, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Stockholm.

EMCDDA and C-EHRN (2023), Drug consumption rooms, Joint report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) and Correlation – European Harm Reduction Network (C-EHRN), Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Hedrich, D., Kerr, T. and Dubois-Arber, F. (2010), ‘Drug consumption facilities in Europe and beyond’, Harm reduction: Evidence, impacts, and challenges, EMCDDA Monographs, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp. 305-332.

Jauffret-Roustide, M. and Cailbault, I. (2018), ‘Drug consumption rooms: Comparing times, spaces and actors in issues of social acceptability in French public debate’, International Journal of Drug Policy 56, pp. 208-217, doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.014.

Kappel, N., Toth, E., Tegner, J. and Lauridsen, S. (2016), ‘A qualitative study of how Danish drug consumption rooms influence health and well-being among people who use drugs’, Harm Reduction Journal 13(1), p. 20, doi:10.1186/s12954-016-0109-y.

Kimber, J., Palmateer, N., Hutchinson, S., Hickman, M., Goldberg, D. and Rhodes, T. (2010), ‘Harm reduction among injecting drug users-evidence of effectiveness’, Harm reduction: Evidence, impacts, and challenges, EMCDDA Monographs, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Körner, H. H. (1993), ‘Strafrechtliches Gutachten zur Zulässigkeit von Gesundheitsräumen für den hygienischen und stressfreien Konsum von Opiatabhängigen’, Az 406/20- 9, ZfB No 507/93, Zentralstelle für die Bekämpfung der Betäubungsmittelkriminalität, Frankfurt am Main.

Levengood, T. W., Yoon, G. H., Davoust, M. J., Ogden, S. N., Marshall, B. D. L., Cahill, S. R. and Bazzi, A. R. (2021), ‘Supervised injection facilities as harm reduction: a systematic review’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 61(5), pp. 738-749, doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.017.

Milloy, M. J. and Wood, E. (2009), ‘Emerging role of supervised injecting facilities in human immunodeficiency virus prevention’, Addiction 104(4), pp. 620-621, doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02541.x.

Pardo, B., Caulkins, J. P. and Kilmer, B. (2018), Assessing the evidence on supervised drug consumption sites, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, doi:10.7249/WR1261.

Potier, C., Laprévote, V., Dubois-Arber, F., Cottencin, O. and Rolland, B. (2014), ‘Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 145, pp. 48-68, doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.012.

Rhodes, T. (2002), ‘The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm’, International Journal of Drug Policy 13(2), pp. 85-94, doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5.

Roux, P., Jauffret-Roustide, M., Donadille, C., Briand Madrid, L., Denis, C., Célérier, I., Chauvin, C., Hamelin, N., et al. (2023), ‘Impact of drug consumption rooms on non-fatal overdoses, abscesses and emergency department visits in people who inject drugs in France: results from the COSINUS cohort’, International Journal of Epidemiology 52(2), pp. 562-576, doi:10.1093/ije/dyac120.

Schäffer, D., Stöver, H. and Weichert, L. (2014), Drug consumption rooms in Europe: models, best practice and challenges, European Harm Reduction Network, Amsterdam.

Semaan, S., Fleming, P., Worrell, C., Stolp, H., Baack, B. and Miller, M. (2011), ‘Potential role of safer injection facilities in reducing HIV and hepatitis C infections and overdose mortality in the United States’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 118(2-3), pp. 100-110, doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.006.

Speed, K. A., Gehring, N. D., Launier, K., O’Brien, D., Campbell, S. and Hyshka, E. (2020), ‘To what extent do supervised drug consumption services incorporate non-injection routes of administration? A systematic scoping review documenting existing facilities’, Harm Reduction Journal 17(1), p. 72, doi:10.1186/s12954-020-00414-y.

Taylor, H., Curado, A., Tavares, J., Oliveira, M., Gautier, D. and Maria, J. S. (2019), ‘Prospective client survey and participatory process ahead of opening a mobile drug consumption room in Lisbon’, Harm Reduction Journal 16(1), p. 49, doi:10.1186/s12954-019-0319-1.

Tran, V., Reid, S. E., Roxburgh, A. and Day, C. A. (2021), ‘Assessing drug consumption rooms and longer term (5 year) impacts on community and clients’, Risk Management Healthcare Policy 14, pp. 4639-4647, doi:10.2147/rmhp.S244720.

Woods, S. (2014), Drug consumption rooms in Europe: organisational overview, European Harm Reduction Network, Amsterdam.

About this miniguide

This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide. It provides an overview of important aspects related to drug consumption rooms, including service delivery, available evidence and what is happening in Europe. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Recommended citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2024), Health and social responses: drug consumption rooms, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications//mini-guides/health-and-socia….

Identifiers

HTML: TD-09-24-251-EN-Q

ISBN: 978-92-9497-967-4

DOI: 10.2810/159981

Source data

The data used to generate infographics and charts on this page may be found below.

| City | Country | lat | lon | Number of facilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brussels | Belgium | 50.84 | 4.35 | 1 |

| Liege | Belgium | 50.6278 | 5.57459 | 1 |

| Aarhus | Denmark | 56.14597 | 10.19845 | 1 |

| Copenhagen | Denmark | 55.67453 | 12.5677 | 2 |

| Odense | Denmark | 55.39509 | 10.38202 | 1 |

| Vejle | Denmark | 55.70232 | 9.522832 | 1 |

| Paris | France | 48.8539 | 2.34879 | 1 |

| Strasbourg | France | 48.579 | 7.73633 | 1 |

| Berlin | Germany | 52.504671 | 13.3945135 | 3 |

| Bielefeld | Germany | 52.02656 | 8.540516 | 1 |

| Bochum | Germany | 51.4815 | 7.2244 | 1 |

| Bonn | Germany | 50.78 | 7.1778 | 1 |

| Dortmund | Germany | 51.56247 | 7.45377 | 1 |

| Düsseldorf | Germany | 51.2397 | 6.6778 | 1 |

| Essen | Germany | 51.4798 | 7.0569 | 1 |

| Frankfurt | Germany | 50.20948 | 8.76 | 4 |

| Hamburg | Germany | 53.56828 | 9.999227 | 5 |

| Hannover | Germany | 52.37608 | 9.73263 | 1 |

| Karlsruhe | Germany | 49.012 | 8.390306 | 1 |

| Köln | Germany | 50.93167 | 6.949464 | 1 |

| Münster | Germany | 51.95222 | 7.623233 | 1 |

| Saarbrücken | Germany | 49.24041 | 6.98665 | 1 |

| Troisdorf | Germany | 50.818 | 7.14125 | 1 |

| Wuppertal | Germany | 51.24225 | 7.158186 | 1 |

| Athens | Greece | 38 | 23.7 | 1 |

| Esch-sur-Alzette | Luxembourg | 49.50245 | 5.97222 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourg | 49.6503 | 6.2512 | 1 |

| Almere | Netherlands | 52.3829 | 5.2887 | 1 |

| Amsterdam | Netherlands | 52.414 | 4.90793 | 3 |

| Apeldoorn | Netherlands | 52.1813 | 6.00827 | 1 |

| Arnhem | Netherlands | 51.98497 | 5.899034 | 1 |

| Deventer | Netherlands | 52.29638 | 6.178408 | 1 |

| Enschede | Netherlands | 52.1988 | 6.87604 | 1 |

| Haarlem | Netherlands | 52.389 | 4.6896 | 1 |

| Heerlen | Netherlands | 50.8888 | 5.9811 | 1 |

| Leeuwarden | Netherlands | 53.1987 | 5.8322 | 1 |

| Leiden | Netherlands | 52.1597 | 4.4811544 | 1 |

| Maastricht | Netherlands | 50.8541 | 5.69063 | 1 |

| Nijmegen | Netherlands | 51.81272 | 5.842056 | 2 |

| Roermond | Netherlands | 51.2248 | 5.9753 | 1 |

| Rotterdam | Netherlands | 51.8882 | 4.6136 | 4 |

| s-Hertogenbosch | Netherlands | 51.69714 | 5.305474 | 1 |

| Tilburg | Netherlands | 51.60593 | 5.14963 | 1 |

| Utrecht | Netherlands | 52.086 | 5.1127 | 1 |

| Vlissingen | Netherlands | 51.42818 | 3.52915 | 1 |

| Zwolle | Netherlands | 52.54429 | 6.09052 | 1 |

| Bergen | Norway | 60.3954 | 5.33062 | 1 |

| Oslo | Norway | 59.920979 | 10.753526 | 1 |

| Porto | Portugal | 41.149 | -8.61 | 1 |

| Lisbon | Portugal | 38.716311 | -9.142432 | 2 |

| Badalona | Spain | 41.450142 | 2.24742 | 1 |

| Barcelona | Spain | 41.3825 | 2.1769 | 9 |

| Bilbao | Spain | 43.2569 | -2.9236 | 1 |

| Lleida | Spain | 41.61898 | 0.6201 | 1 |

| Reus | Spain | 41.14994 | 1.10571 | 2 |

| Sant Adrià de Besòs | Spain | 41.430599 | 2.21824 | 1 |

| Tarragona | Spain | 41.1186 | 1.24047 | 1 |